Facial expression analysis: Dr. Nicolas Hamelin talks about emotions & advertising effectiveness

Total advertising spending in the US is on an ever-increasing curve. In 2014 American businesses spent over B$180.12 (Emarketer, 2015). Globally in 2015 over B$540 billion was spent on advertising, a 4.6% increase over 2014 (Adage, 2015) with the general public being exposed to an increasing number of the ad. In 1985 the urban American would see around 2,000 ads per day with this number shooting up to 5,000 ads per day in 2016 (NY Times, 2015). Yet out of a sample of 350 ads watched per day only 153 ads would receive attention for more than a few seconds (SJ insight, 2014). Measuring advertising effectiveness has always been the greatest challenge of marketing and advertising professionals. There are two main methods for measuring advertising effectiveness: One focuses on measuring indicative marketing metrics such as awareness, preference, customer satisfaction, loyalty, and the other focuses on measurement of tangible marketing metrics such as sales, market share, profits, return on investment, cash flow, firm value. The complexity of measuring advertising effectiveness increases if the variable “emotion” is introduced. An emotional message in advertisements increases the audience attention toward the ad and product, boost product attractiveness, and generates a higher level of brand recall and various research have found that that emotion is a predictor of advertising effectiveness. There are various methods to evaluate emotion in advertising research. The emotional response can either be measured using self-report or autonomic measure. The visual self-report requires the respondent to choose a cartoon character matching his or her emotional state, while in verbal self-report respondents answer an open-ended question or rate their emotional state on a Likert-type scale. Self-reports usually capture the conscious state of the individual while the autonomic capture the body’s reactions. Body’s reactions such as heart rate fluctuation, or variation in skin acidity are most of the time beyond the conscious control of the individual while self-report or surveys suffer from heavy bias, for example, the Theory of Social Desirability posit that interviewees will tend to avoid socially unacceptable responses or will tend to provide answers which he or she perceives to be matching the value system of the interviewer. SPJAIN Neuroscience lab uses noninvasive facial recognition software to investigate the potential link between emotion and advertising effectiveness. Facial muscle involved in expressions are linked to the cerebral cortex through the corticobulbar track and reflect the activation of the brain’s amygdala region which is responsible for all potential value of all facial expression. In this research we uses GFK-EMO Scan, facial recognition software developed by Munich based Franhofer institute. GFK-EMO can record over 20 frames per second enabling an accurate measure of real-time emotional responses. Two safe driving ads from the UK were shown to a group of 60 participants and their emotional reaction were recorded. Both ads convey the same message about the danger of speed and road safety. While one ad used a highly affective message strategy, the other ad relies mostly on rational strategy. The high emotional video presents a dramatic car accident with casualties, and convey a high level of negative emotions including grief, fear, and shock. The low emotional ad delivers scientific facts about the danger of speed. Right after watching the ads and two weeks after watching the ads the students were requested to answer a survey adapted from the National Survey of Speeding Attitudes and Behavior (NSSAB).

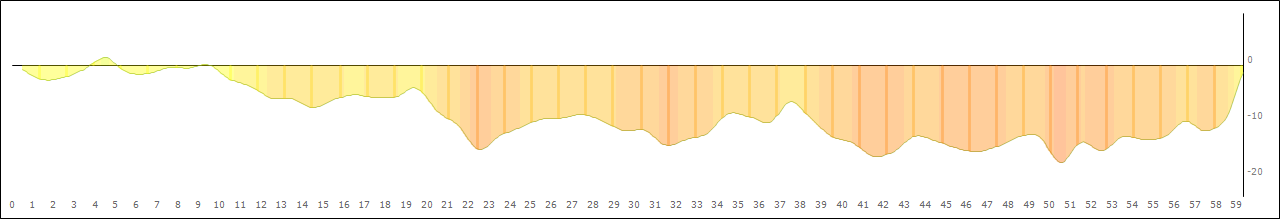

The Figure below shows the median emotional values of a group who was shown the high emotional video. The first seconds of the ad show a young couple kissing and not surprisingly a positive emotion is recorded. But immediately after this scene, a car hits the couple and the emotional valence turns negative and remains negative until the end of the ad.

A first result from our study suggests that response to an advertising is constant across a given population. Although there a noticeable variation was noted between genders, both male and female have an identical emotional reaction to a given stimulus. Another key finding of this study pertains to the impact of high emotional vs low emotional ad: Respondents subjected to highly emotional stimuli while watching the high emotional ad reported better safe driving attitude score than a respondent who had watched the more rational, less emotional ad. Regarding memory effect this study also showed that high emotional ad lead to a more stable attitude change that low emotional ad. Safe driving attitude score of respondents who had watched the low emotional ad dropped significantly after two weeks, respondents who had watched the highly emotional ad maintained the same high score after two weeks. Hence message conveyed within an emotional strategy appears to benefit from better storage and retrieval than the same message transferred through a low emotion strategy This study support previous finding regarding the prevailing role of emotion in the human’s cognitive process. Ledoux has showed that there is a high density of upward communicative pathways going from amygdala, to the cortex but no downward connection from the cortex to the amygdala. In other words, emotions can control thoughts and action whereas the reverse is not true. Implications are far reaching both in term of advertising effectiveness and ethical issue. Firstly, emotional advertising is clearly able to foster a relatively strong and enduring attitude and behavioral change in an audience. A second implication pertains to the measurement of the effectiveness of an ad. Traditional way of measuring if an ad is effective is a costly exercise that is generally done post campaign and relies on gathering data from many respondents. Marketers can use facial detection on a much lower number of subject to obtain information that would otherwise not be obtainable through traditional marketing research techniques to predict the efficiency of a campaign before its launched. Last but not least, there is indeed an obvious moral issue behind “finding the ‘buy button in the brain’ and … creating advertising campaigns that we will be unable to resist” (Editorial, Nature Neuroscience, 2004 p. 683). The author wish to thanks Dr Othmane el Moujahid for his contribution to this research.

About the Author:

Dr. Nicolas Hamelin holds a PhD in Physics from Sussex University in the UK, an M.Sc. in  Environmental Management from Ulster University and is a PhD candidate in Business at the Royal Docks Business School, University of East London. After completing his Undergraduate studies in France, Dr. Hamelin has been based out of Amsterdam, Italy and America, the experience of which he incorporates in his teaching. Having worked in several corporations including Phillips and Nokia, he is now an in-country analyst for Euro monitor International, a London based global marketing research agency. His main research interests are in the fields of International Marketing, Consumer Behaviour, Neuro-Marketing, Social Marketing and Environmental Management. Dr. Hamelin is currently working with S P Jain School of Global Management as an Associate Professor for Marketing.

Environmental Management from Ulster University and is a PhD candidate in Business at the Royal Docks Business School, University of East London. After completing his Undergraduate studies in France, Dr. Hamelin has been based out of Amsterdam, Italy and America, the experience of which he incorporates in his teaching. Having worked in several corporations including Phillips and Nokia, he is now an in-country analyst for Euro monitor International, a London based global marketing research agency. His main research interests are in the fields of International Marketing, Consumer Behaviour, Neuro-Marketing, Social Marketing and Environmental Management. Dr. Hamelin is currently working with S P Jain School of Global Management as an Associate Professor for Marketing.